Some viruses roar like lions—fast, fierce, and obvious. Others move like shadows—quiet, patient, and devastating. HIV is one of these silent invaders. It doesn’t storm the body overnight. Instead, it creeps in, takes its time, and slowly dismantles the immune system from within. That’s because HIV belongs to a unique family of viruses known as lentiviruses—from the Latin word “lenti,” meaning slow.

To understand the journey of HIV, and ultimately answer the question “AIDS – where did it come from?”, we must first understand what makes a lentivirus so different—and so dangerous.

Unlike the common cold that comes and goes in days, lentiviruses are built for the long game. They are a type of retrovirus, which means they carry their genetic material in RNA and insert themselves into a host’s DNA. But lentiviruses do it slowly, methodically. They establish a lifelong presence, quietly hijacking the immune system while showing few, if any, symptoms for years.

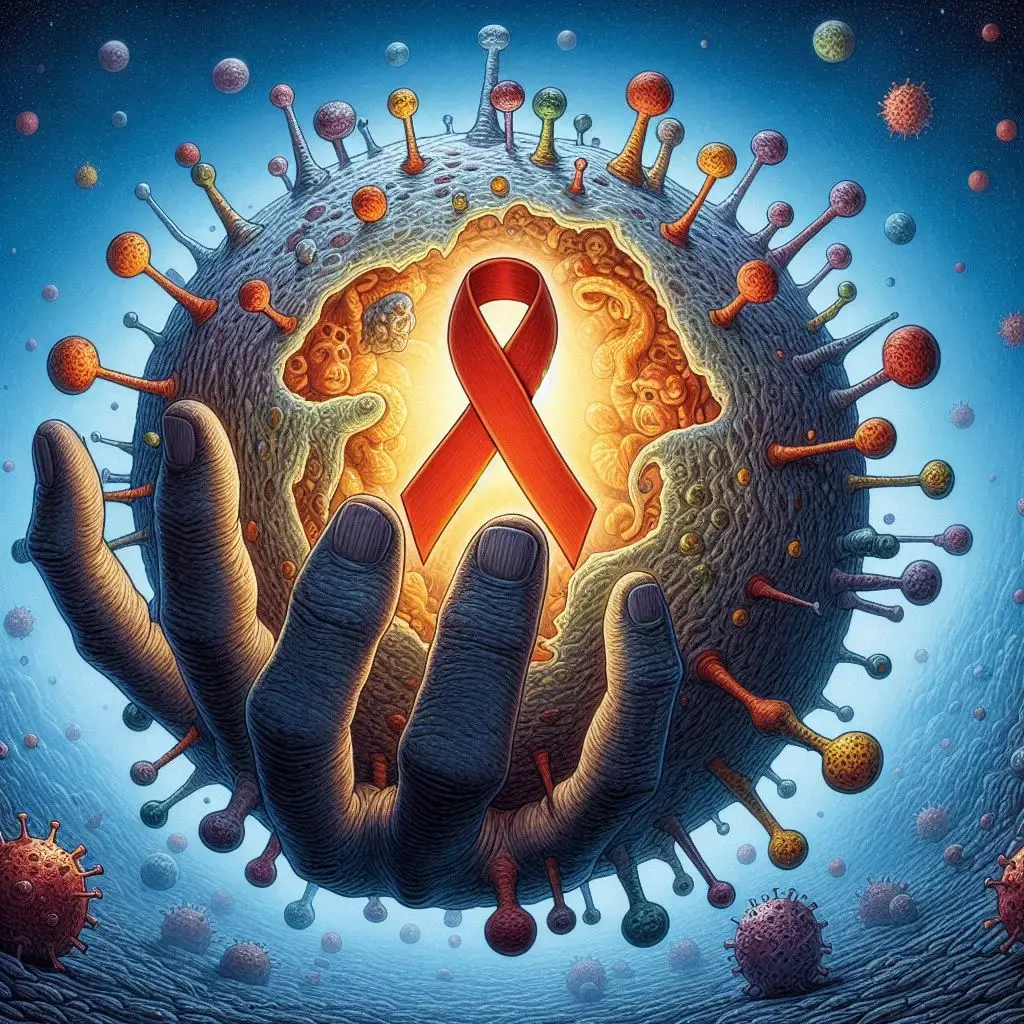

Once inside the human body, it targets CD4 cells, the very generals of our immune system. It doesn’t kill them instantly. Instead, it silently weakens them over time, often over the course of a decade, before the body’s defenses finally collapse. That collapse is what we call AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome).

But how did such a virus find its way into the human bloodstream? AIDS – where did it come from?

The story begins not in the laboratory, but in the lush forests of Central Africa. There, among the trees, live chimpanzees infected with a close cousin of HIV—SIV (Simian Immunodeficiency Virus)—another lentivirus. Through the bushmeat trade, where wild animals are hunted and butchered for food, SIV made its leap into humans, likely through cuts and exposure to infected blood. This cross-species transmission gave birth to HIV.

However, it wasn’t just the virus’s nature that allowed it to spread. The environment was ripe. In colonial Africa, especially in urban centers like Kinshasa, population movement, unscreened medical practices, and poor health infrastructure allowed this slow-acting virus to travel undetected. By the time HIV had reached the global stage in the 1980s, it had already spent decades working silently in the shadows of human populations.

This is the genius—and horror—of a lentivirus. Its quietness is its strength. It’s not a blitz attack—it’s a siege.

we are not just asking about chimpanzees, or a hunter, or a city. We are asking about a virus designed to hide, wait, and dismantle. A virus that evolved to spread before striking. A virus that moves with the patience of time itself.

Yet understanding HIV as a lentivirus has given us powerful tools. Scientists now know that though lentiviruses act slowly, they can be slowed even further—stopped, even controlled—with antiretroviral therapy (ART). These treatments don’t cure HIV, but they hold it in place, preventing progression to AIDS. In essence, we’ve learned to match patience with precision.

The deeper lesson is this: just because something moves slowly doesn’t mean it’s harmless. HIV taught us that. It redefined how we understand viruses and public health. And it continues to shape global medicine today.

In the end, the story of HIV is not just a story of disease—it’s a story of evolution, of silence, of delay. It’s the story of a lentivirus that reshaped human history, one quiet moment at a time.

And when we reflect and ask again, “AIDS – where did it come from?”, we now know the answer lies not just in where it began—but in how it behaves.