Picture your body as a great nation, constantly under threat from unseen invaders—bacteria, viruses, and parasites. In this kingdom, the immune system is the military, and among its ranks, the most important officers are the T-helper cells. These specialized white blood cells are the generals, the ones who plan the strategy, rally the troops, and signal when and where to attack.

Now, imagine what happens when an enemy targets the generals first. That is exactly what HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) does. It doesn’t go after the common soldiers. Instead, it locks on to the T-helper cells, invades them, and begins to destroy them from the inside out. Without these generals, the entire immune army is left confused and vulnerable. This targeted attack lies at the heart of a devastating question the world has asked for decades: AIDS—where did it come from?

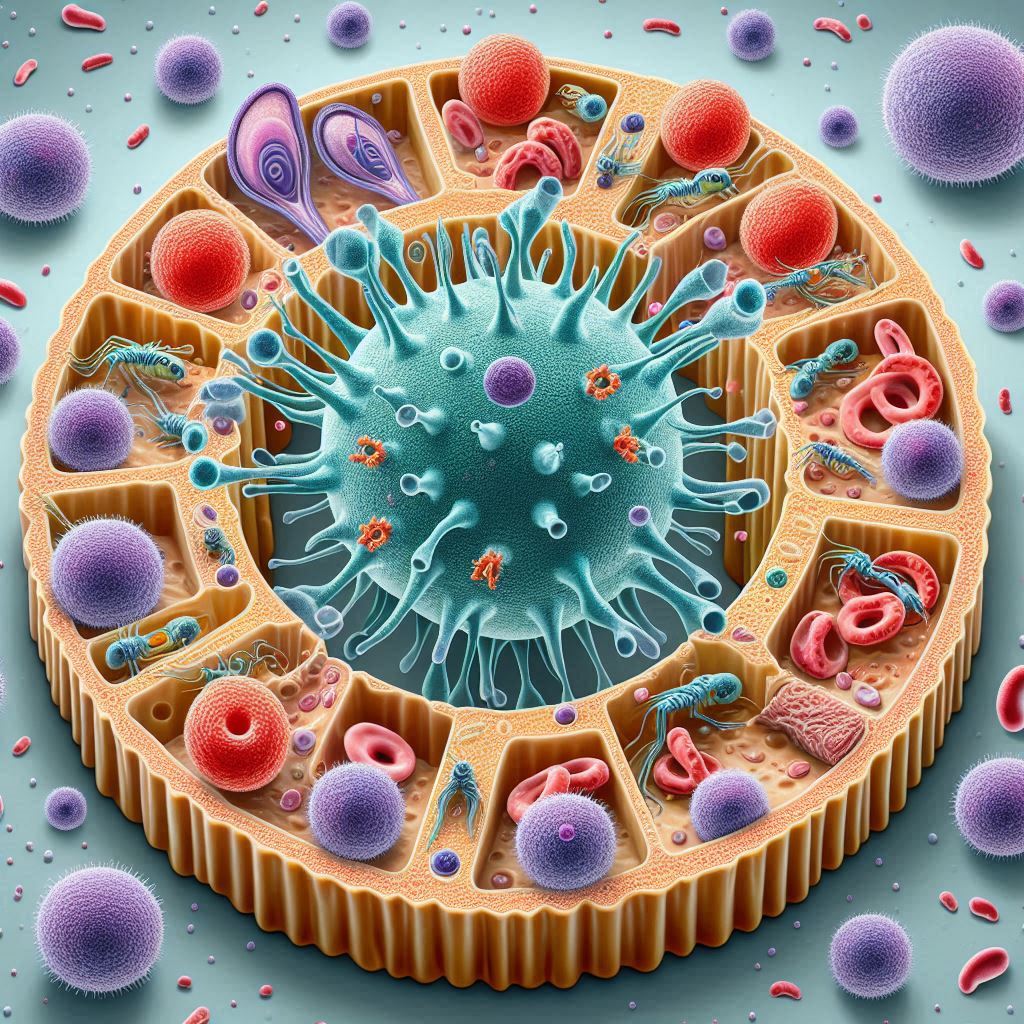

The T-helper cells, also known as CD4 cells, are the orchestrators of immune defense. They coordinate the battle, ensure the right responses, and maintain control.

It attaches itself to these cells, injects its genetic code, and hijacks their machinery to create more copies of itself. After making use of the cell, HIV destroys it, leaving the immune system weaker with every passing day.

In the early days of infection, a person might not notice anything wrong. The immune system puts up a fight, and T-helper cells work hard to contain the virus. But over time, as more and more of these critical cells are lost, the immune system begins to falter. It’s like a nation whose leaders have vanished—panic, disorder, and vulnerability follow.

This is where the connection to AIDS becomes clear. When T-helper cells drop to dangerously low levels, the body can no longer fight off diseases it once easily resisted. Even a minor infection or a common cold could now prove life-threatening. And so the terrifying progression from HIV to AIDS is marked by the disappearance of T-helper cells—the very backbone of immune intelligence.

So, AIDS—where did it come from?

It began not just as a virus crossing from chimpanzees to humans in the early 20th century in Central Africa, but as an invisible war on the immune system’s command center. HIV’s ability to target and destroy T-helper cells is what makes it so uniquely deadly.

Modern medicine now uses antiretroviral therapy (ART) to keep HIV under control. These treatments don’t kill the virus outright, but they can suppress it, allowing T-helper cells to recover and continue protecting the body. With early diagnosis and consistent treatment, people with HIV can avoid developing AIDS, maintaining their immune strength for decades.

But the lesson remains clear: understanding T-helper cells is crucial to understanding how HIV works and why the question “AIDS where did it come from?”

In the end, it’s not just about a virus—it’s about the quiet battle within, the loss of leadership in the immune army, and the global efforts to reclaim control. The story of T-helper cells is the story of resistance, vulnerability, and the fight for survival.