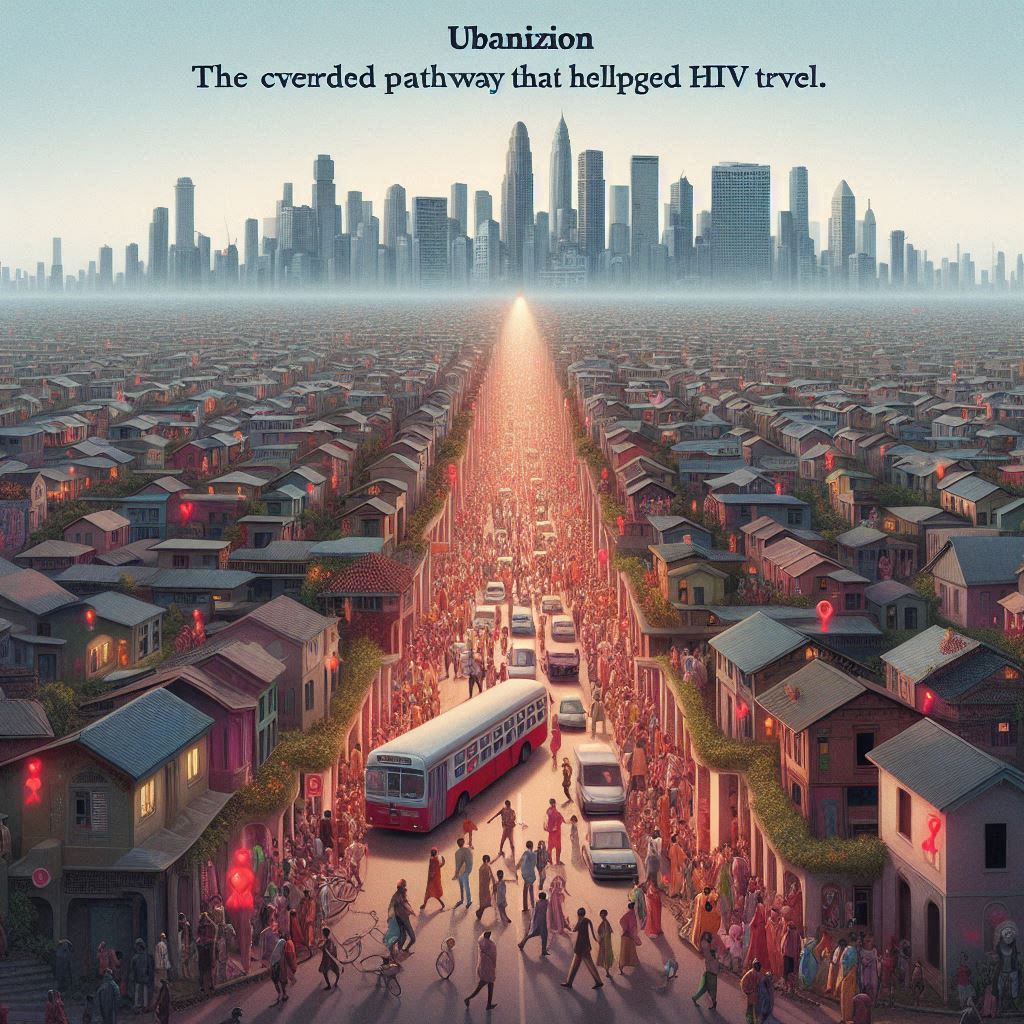

Imagine a small village, peaceful and self-contained. People know each other by name, life moves at a gentle pace, and news travels slowly. Now imagine that same village transformed into a buzzing city, full of people, vehicles, strangers, opportunity—and risk. That transformation is urbanization: the rapid growth of cities, which, while bringing progress, also creates new ways for diseases to spread quickly and quietly.

When discussing the global HIV/AIDS crisis, one question still echoes across time: AIDS—where did it come from? While the virus (HIV) may have originated in Central Africa, likely jumping from chimpanzees to humans in the early 20th century, its silent spread was aided by something very human—urbanization.

To understand this, let’s picture HIV as a whisper. In small, rural communities, that whisper is easy to contain. But in a large, noisy city, the whisper becomes a shout, echoed and amplified by millions. Urbanization created the perfect storm for that shout to be heard worldwide.

In the early 1900s, Africa began to undergo massive change. Colonial rule, railway construction, and economic shifts brought thousands of people from small villages into growing urban centers. Cities like Kinshasa (formerly Léopoldville) in the Democratic Republic of Congo exploded in size. With that growth came crowded living, poor sanitation, and limited healthcare—ideal conditions for disease to spread.

But the story doesn’t stop there.

Urbanization also brought social disruption. Men left their families in villages to work in cities. In these new environments, sex work increased, and so did the number of sexual partners people had—both of which are key factors in the early spread of HIV. In these fast-growing, disconnected urban landscapes, the virus found more hosts, more movement, and more momentum.

And so again we ask: AIDS—where did it come from?

It came not just from the jungle, but from the streets of growing cities, from the train lines that connected villages to ports, and from the human desire for opportunity that urbanization promised.

As people moved, so did the virus. In cities with limited infrastructure, blood transfusions were often unscreened, medical tools reused, and needles shared. All of this allowed HIV to multiply—quietly at first, then loudly as symptoms and deaths began to rise.

Even in modern times, urban areas remain hotspots for HIV transmission. Dense populations, anonymous interactions, and disparities in healthcare access continue to create risk. However, cities are also where prevention efforts, education campaigns, and medical research have taken root and flourished. Urbanization may have helped ignite the epidemic, but it also provides tools to fight it.

Today, with improved urban planning and access to healthcare, many of the risks can be reduced. Public awareness programs, free testing centers, condom distribution, and antiretroviral therapy are far more accessible in urban settings than in remote villages.

Still, the early connection between urbanization and the spread of HIV remains a lesson for the future. It teaches us that when cities grow without attention to public health, the cost can be invisible—but devastating.

So when someone wonders, AIDS—where did it come from?, the answer is layered. It began with nature, spread through blood, and grew in the shadows of urban development. Urbanization didn’t create HIV, but it helped the virus find its legs, its roads, and eventually, its wings.

Understanding the role of urbanization in HIV’s journey isn’t just a historical exercise—it’s a roadmap for building healthier, safer cities today.