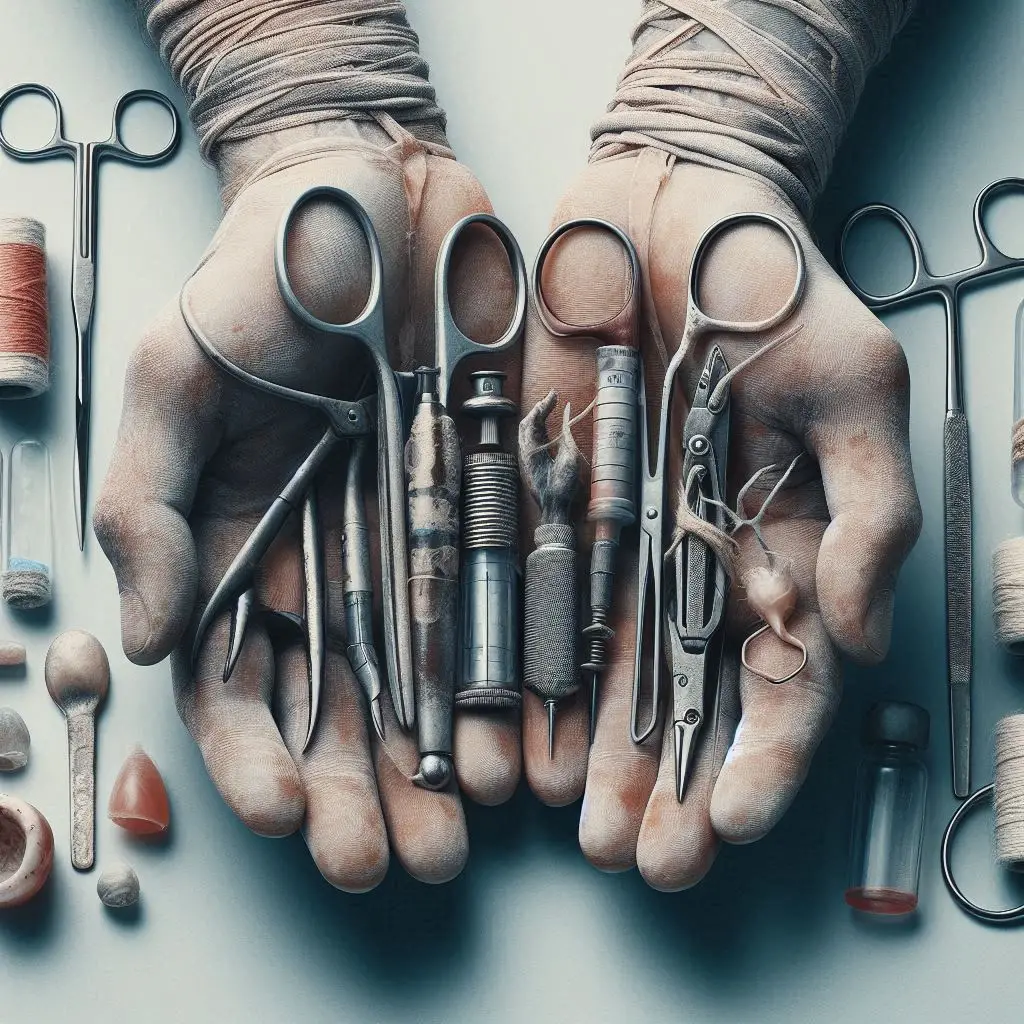

Imagine a locksmith, trusted to secure every door in the village. His tools shine, his hands are skilled—but what if, without knowing, he uses the same key on a door infected with poison, then uses it again and again? Each time, he means to protect, but unknowingly spreads danger. This is what happened when unsterilized medical tools became quiet agents in the early spread of HIV.

When people ask, AIDS—where did it come from?, they usually think of forests, viruses, and the leap from animals to humans. While that is part of the story, the unintended role of medicine itself, particularly in under-resourced regions, also played a crucial part. In hospitals and clinics meant to heal, reused syringes, needles, and surgical tools sometimes passed HIV from one patient to another, silently and invisibly.

In the mid-20th century, as urbanization and migration accelerated across Africa and other developing regions, access to healthcare began to expand. Clinics popped up in cities and towns. But while intentions were noble, resources were limited. In some areas, a single syringe was used for dozens of patients—washed with water, wiped with alcohol, or sometimes not cleaned at all.

Let’s understand this through another metaphor.

Imagine a paintbrush used to create beautiful art. But if dipped in poisoned paint once and reused without washing, it spreads that poison across every canvas. Medical tools, when not properly sterilized, acted exactly like that brush. A single HIV-positive patient could unknowingly leave behind a viral trace on a syringe or scalpel. The next patient—trusting, unaware—would receive more than just treatment.

And so, AIDS—where did it come from?

Not only from the wild, but from the gaps in health systems, the shortages of clean supplies, and the overuse of unsterilized equipment. In many areas, routine vaccinations, dental work, and even childbirth assistance may have unknowingly involved the reuse of contaminated instruments.

What makes this so tragic is that the people most affected were often those trying to stay healthy—those seeking care for minor illnesses or children being vaccinated. Unlike risky behaviors that involve choice, these were acts of trust—trust that was betrayed by poor infrastructure and lack of training.

It’s important to recognize: the doctors and nurses weren’t villains. They worked in overcrowded clinics with little equipment, long lines of patients, and immense pressure. Often, they were never trained on proper sterilization techniques, or lacked even the basic tools like autoclaves (medical sterilizers). The true enemy was the lack of education, funding, and international attention.

Today, thanks to global awareness and better investment in healthcare, the use of single-use needles and proper sterilization protocols is standard in most parts of the world. But in some rural or conflict-stricken regions, unsafe practices still occur, and the risk of bloodborne infections like HIV remains real.

So once again, we ask: AIDS—where did it come from?

It came from the intersection of biology and human systems—from a virus born in nature, and spread by the tools we built to protect ourselves. The tragedy of unsterilized medical tools reminds us that even healing hands can harm if not properly equipped.

This part of the AIDS story is not meant to blame, but to teach. It teaches us that safety in medicine is not a luxury—it is a necessity.

In the fight against HIV, understanding the role of unsterilized tools is key to answering the bigger question: AIDS—where did it come from, and how do we keep it from coming again?