It didn’t arrive with sirens or spotlights — it arrived quietly, like a teacher in a noisy class, offering answers where there was only confusion. In a world filled with frightened whispers asking, “AIDS — where did it come from?”,

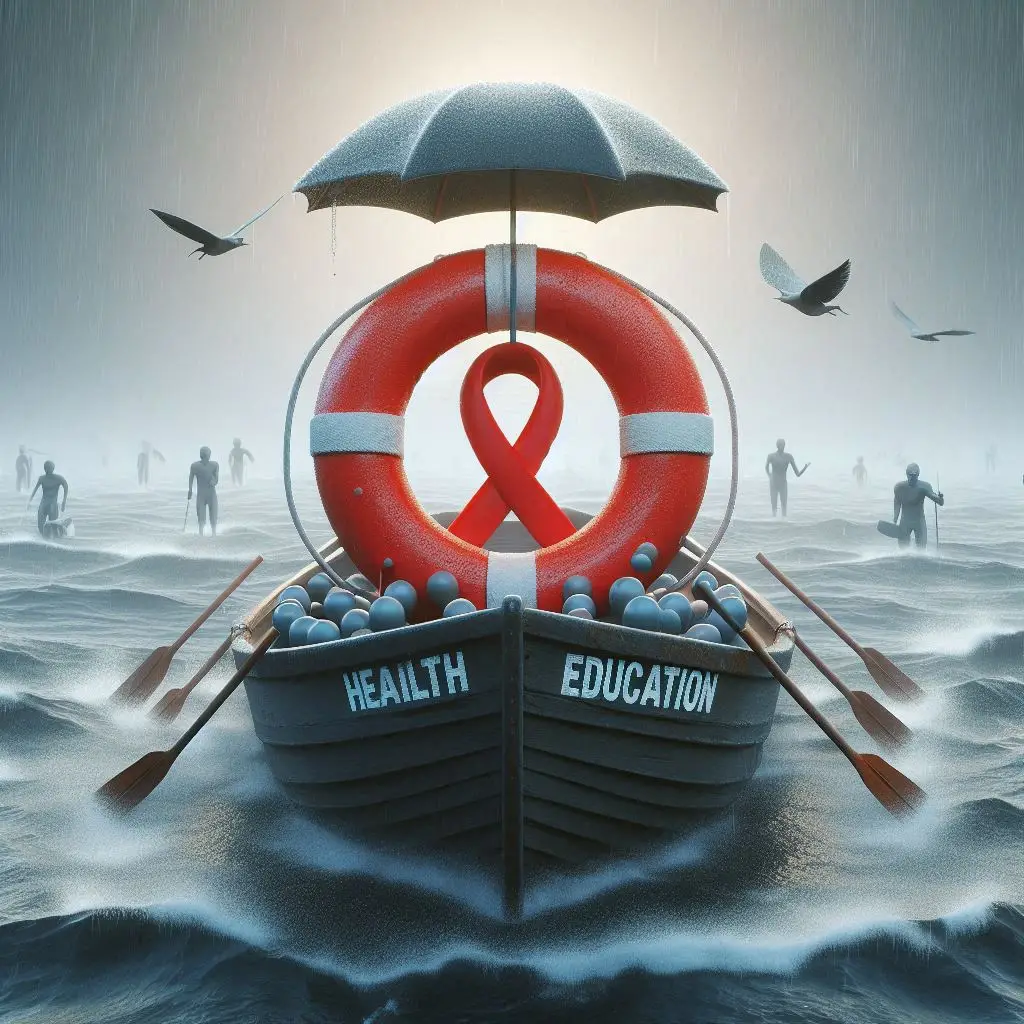

Imagine a ship lost at sea. The wind is fierce, the sky is dark, and no one knows which way is land. That ship was our global society when AIDS emerged. Rumors became the sails, panic the waves, and misinformation the anchor. People knew they were in danger, but not how to save themselves. And then came health education — not a storm, but a steady hand on the wheel.

In the early years, the world didn’t just lack answers about HIV — it lacked understanding. Instead of looking forward, many were looking to blame. It wasn’t science leading the discussion — it was stigma. People didn’t know how the virus spread, but they were certain who to fear. Health education flipped that script.

From posters in clinics to lessons in classrooms, from campaigns on television to quiet conversations in community centers — health education brought clarity. It taught the world that HIV is not a curse, not a judgment, not a mystery — but a virus. One that could be understood. One that could be prevented.

At its heart, health education is empowerment. It doesn’t just tell people what to do — it explains why. It equips minds with facts instead of fear. For example, teaching that HIV spreads through specific bodily fluids — not casual contact — removed the myth that a handshake or shared glass could be deadly. Suddenly, people living with HIV were no longer outcasts; they were neighbors, coworkers, family members — treated with dignity, not suspicion.

education shifted the focus from origin to action. It taught that the real question was: “How do we stop it?” And answers followed — safe sex practices, regular testing, avoiding needle sharing, understanding treatment options, and eliminating stigma. These weren’t just lessons; they were life jackets.

Programs like peer education in schools, community outreach in rural villages, and workplace awareness seminars began to change the tide. Countries that invested in health education saw drops in infection rates. People began to seek testing early, talk openly, and make informed choices. Where silence once ruled, dialogue blossomed.

The beauty of health education is that it evolves. It meets people where they are — be it in a slum, a university, or online. Modern strategies include digital campaigns, interactive apps, and youth-led initiatives — all aiming to keep the next generation not just HIV-free, but HIV-aware.

But perhaps the greatest victory of health education was that it replaced shame with strategy. It taught people that they didn’t need to ask in fear, “AIDS — where did it come from?”, but rather in wisdom, “How can I protect myself and others?” It turned helplessness into hope.

Today, health education remains our strongest shield. It doesn’t require a prescription, and it doesn’t expire. In the ongoing journey against HIV, it continues to be the compass steering us toward a safer shore.

So when the question rises again — “AIDS — where did it come from?” — let the answer begin with knowledge, carried forward by education, and planted in the soil of understanding.