History is full of loud wars and quiet epidemics. While flags were raised and borders redrawn in Colonial Africa, something else was unfolding in the shadows—something invisible, something that wouldn’t be noticed for decades. Today, as the world still asks “AIDS – where did it come from?”, the answer lies partially buried in the dust of colonial roads, the rust of reused needles, and the silence of medical records never written.

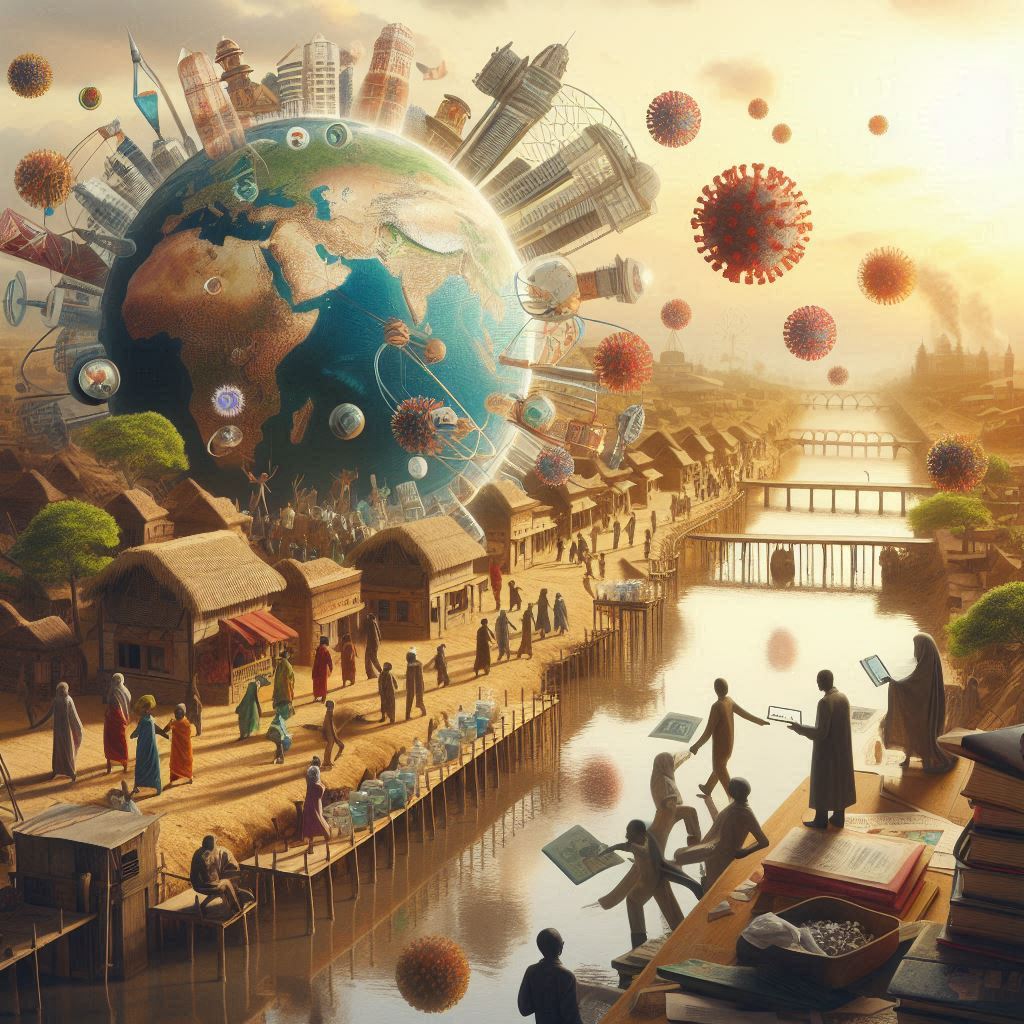

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, European powers carved Africa like a pie—Belgium, France, Britain, and others staking their claim to land, people, and resources. But what came with colonization wasn’t just railways and rubber plantations. It also brought new patterns of human movement, forced labor, urban crowding, and rudimentary health systems that often did more harm than good.

Picture this: a young man from a forest village conscripted to work in a colonial city like Kinshasa, a rising urban hub. Along his journey, he may have interacted with wildlife, including chimpanzees—unknowingly exposing himself to SIV, the Simian Immunodeficiency Virus. When SIV entered his body through a hunting wound or bushmeat consumption, it began its quiet transformation into HIV.

Colonial healthcare often meant mass injections with unsterilized equipment, as European doctors attempted to manage tropical diseases with limited supplies. One syringe might be used on dozens of patients without proper cleaning. In these colonial outposts, medicine walked hand in hand with ignorance. And through these needles, HIV likely spread from the first few infected individuals into wider populations—long before anyone knew such a virus existed.

So, AIDS – where did it come from?

It came not just from the jungle, but from a system that valued control over care. It came from medical camps where quantity often overshadowed caution. It came from cities hastily built to serve colonial economies, where sex work, poverty, and migration thrived in crowded corners.

Moreover, colonial rule disrupted local cultures and healing traditions, replacing them with systems that were alien and often unsafe. Traditional healers were banned or ignored, replaced by clinics with good intentions but bad practices. This created the perfect storm—viral transmission accelerated by institutional neglect.

HIV didn’t emerge from thin air. It followed the paths carved by colonial roads, railways, and riverboats. It moved with people—laborers, soldiers, nurses—traveling across Central Africa, incubated silently by the very systems that claimed to bring civilization.

Only much later, in the 1980s, did the virus gain a name: HIV. And its consequence: AIDS. But by then, it had already passed through generations, its true beginning long forgotten by most.

So when the question echoes again—“AIDS, where did it come from?”—the honest answer reaches beyond virology and into history. It came from the meeting of wild blood and steel needles. From empire and medicine. From silence and oversight.

Today, this knowledge serves as a powerful warning. Public health is not just about curing disease—it’s about understanding the systems that allow disease to spread. Colonial Africa may be a page in the past, but its legacy lives on in the global map of HIV.

In remembering how AIDS came from the very heart of colonial expansion, we learn how deeply our health is tied to justice, history, and humanity. Because the virus didn’t just exploit biology—it exploited broken systems.